The best celebrations bring people together in fellowship, offer moments of reflection, spark meaningful conversations, and create joyful memories. I hope you enjoy what we should all consider a special day, along with another thoughtful Independence Day article from Evergreen.

Past Independence Day Articles:

What Does Freedom Mean – Explains what our founders knew they were sacrificing, and an inspiring story.

The Black Robe Regiment – The history of the famous preachers of the revolution, who the British called the “Black Robe Regiment.

Founding Frenemies – The story about the great friendship & conflict of two of the most famous founders of our country.

Divine Preservation – The story of the fascinating preservation of the “Father of the Nation” and the original Commander-in-Chief.

Slavery & the Original Declaration of Independence – The original Declaration of Independence was voted down because of the disagreements over slavery.

The Founding of our Freedom – We review where our Founders’ ideas of our freedoms came from.

Principles of George Washington – We highlight a few of Washington’s most noble values that we should embody.

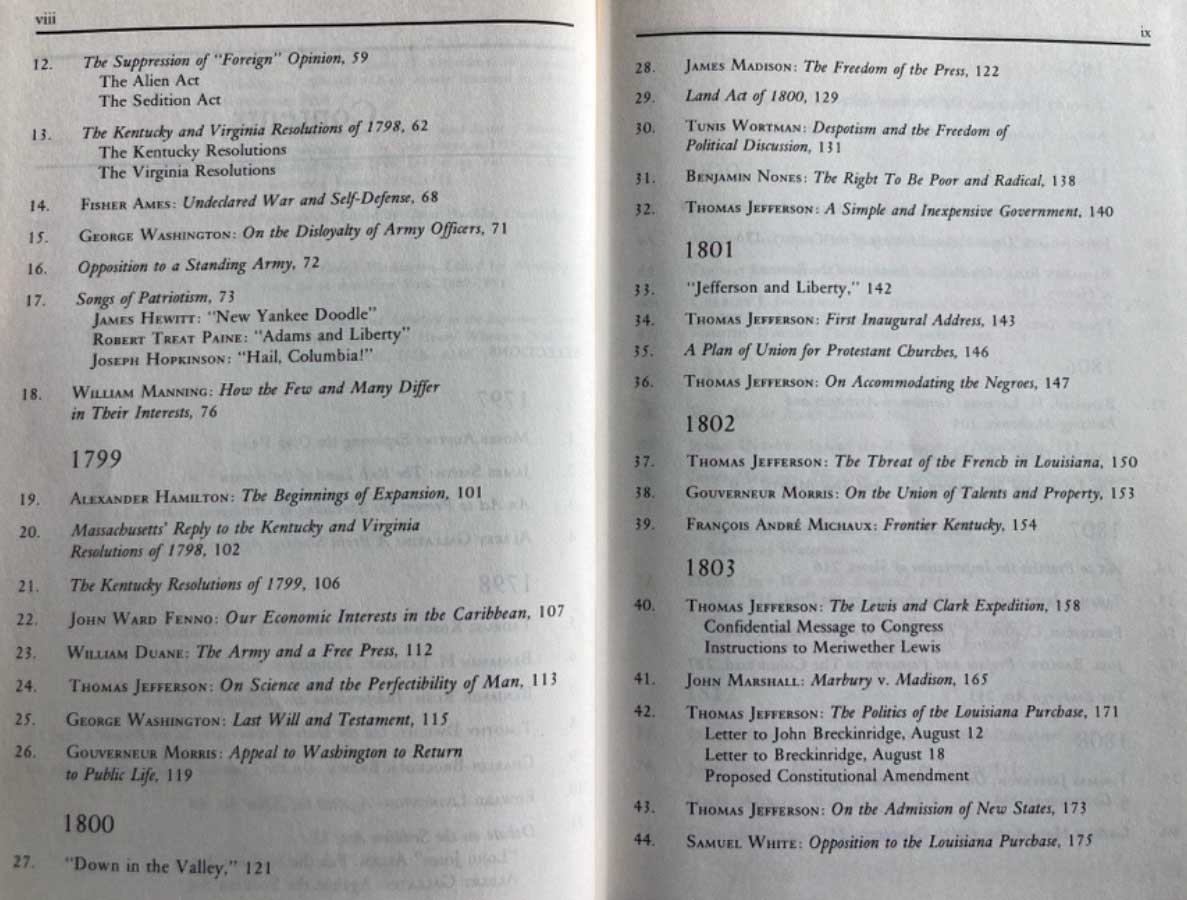

As someone who truly enjoys learning, I have a decent-sized bookshelf. A part of it contains a series called The Annals of America—a collection of original writings from specific periods in American history. Each volume is organized chronologically, with the author and the major topic of each piece clearly identified.

As I strive to do in all my articles, I believe we should always seek information as close to the original source as possible.

Volume 4 of the book series is titled “Domestic Expansion and Foreign Entanglements.” This is between the years of 1794-1820. The public and political discussion of foreign entanglements has grown recently, which encouraged me to look through this book. What was the stance of our country on various foreign conflicts?

Founding Fathers’ Stance on Foreign Entanglements

George Washington: 1794, 1796

One of the earliest foreign conflicts, known as “The Neutrality Crisis,” the United States encountered in 1793 with a war between Great Britain and France. Some would assume, since we won a war with Great Britain in 1783, that we would support the French who supported us during the Revolution. To some people’s surprise, there was a division between staying out of their conflict, supporting France, and whether the US should support Great Britain.

Founders such as Thomas Jefferson and James Madison wanted to support the French, while Alexander Hamilton supported neutrality. Ultimately, Washington would sign the Neutrality Act of 1794 into law, which prohibited any U.S. citizen from engaging in military action against any nation at peace with the U.S. (1). Thomas Jefferson would resign as Secretary of State with this disagreement.

I wrote about Washington’s 1796 Farewell Address in Divine Preservation. In his Farewell Address to the nation, he has a lengthy section on how we should look at foreign conflicts. Saying, “The great rule of conduct for us… is as little political connection as possible.” Exercising, “good faith and justice towards all nations.” “Steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world.” In other words, fulfill our obligations and cease partnerships. However, we may have “temporary alliances, for extraordinary emergencies.” Washington’s stance was to have as few conflicts and alliances with other countries as possible. (2)

Fisher Ames: 1794-1798

I spoke about Fisher Ames in The Founding of Our Freedom. He was a Massachusetts representative at the Constitutional Convention, served in the first four Congresses, helped shape the Bill of Rights, and is credited with the language of the First Amendment.

Ames supported Washington’s neutrality policy but later developed negative views of France. In 1794, he gave an important speech in the House opposing James Madison’s proposal to declare war against Britain. Then, in 1796, he would give another persuasive speech in the House to help support the approval of the Jay Treaty, which reaffirmed good relations with the British. (3)

By 1798, his attitude changed to a more aggressive stance towards France. During John Adams’ presidency, we had a “quasi-war” with France. He wrote a letter to the Secretary of State about his opinion on dealing with this new conflict. Ames viewed France as a military and ideological threat to the country. Although arguing not to declare war, “We had better begin at the tail of the business and go on enacting the consequences of war, instead of declaring it at once.” (4)

Ames argues that waiting for a formal declaration of war could be disastrous. “My long letter amounts to this: we must make haste to wage war, or we shall be lost.” He qualifies this by emphasizing that it should be done reluctantly and with a defensive posture; “Let it be said that we deprecate war, and will desist from arms, as soon as her acts shall be repealed… We should need no negotiation to restore peace.” In other words, we should make aggressive military stances of self-defense, and in the meantime, prepare for war. If French relations improve, the U.S. should pull back its military aggressiveness. (4)

Thomas Jefferson: 1801- 1802, 1813

In Thomas Jefferson’s First Inaugural Address in 1801, he says, “Peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations; entangling alliances with none.” Like Washington, Jefferson believes in temporary alliances, avoiding permanent political or military commitments. When going over the principles of our republic, he mentions “… well disciplined militia, our best reliance in peace and for the first moments of war till regulars may relieve them…” Supporting the citizens’ right to bear arms and having a military capable at any moment to fight is necessary for our republic. (5)

In 1802, Jefferson wrote a letter to the U.S. minister of France expressing deep concern with France’s purchase of Louisiana from Spain. Jefferson viewed this and other actions that France took as a threat to American security, trade along the Mississippi, and western expansion. He warns, “The day that France takes possession of New Orleans… we must marry ourselves to the British fleet and nation.” (6) It was only eight years prior that Jefferson supported France over the British. He then changed his position because he believes it is in the country’s best interest. It’s not that Jefferson wanted to “marry” meaning permanent alliance, but to secure a strong temporary alliance so the position of the U.S. would improve towards the French.

As President, Jefferson insists the United States must prepare for war, though he prefers peaceful negotiation. He writes, “We must make haste to wage war, or we shall be lost,” but qualifies that any such action must be grounded in self-defense and self-preservation, not aggression. He urges diplomatic efforts with France, asking that they either relinquish New Orleans or ensure it does not interfere with American trade and peace. (6) This was the beginning of the U.S.’s eventual purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France.

While America was at war with Britain in 1813, Jefferson wrote a letter to a famous German geographer speaking about various topics, such as the Mexican War of Independence, the War of 1812, and the idea of the American continent separating itself from Europe. He writes about the Mexican War, “But in whatever governments they end, they will be American governments, no longer to be involved in the never ceasing broils of Europe.” He continues:

“The European nations constitute a separate division of the globe; their localities make them part of a distinct system; they have a set of interests of their own in which it is in our business never to engage ourselves. America has a hemisphere to itself. It must have its separate system of interests, which must not be subordinated to those of Europe. The insulated state in which nature has placed the American continent should so far avail it that no spark of war kindled in the other quarters of the globe should be wafted across the wide oceans which separate us from them.” (7)

Jefferson argues that the U.S. must maintain its own distinct set of interests and avoid being entangled in the power struggles of European nations.

John Quincy Adams: 1820

In 1820, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams warned against the U.S. getting involved in Europe’s political or military affairs. He wrote to the U.S. minister in Russia, criticizing Europe’s alliance systems as power games between rulers rather than righteous causes.

Adams affirms the U.S. should stay away from such alliances, stating the United States is “essentially pacific in temper” and must “stand in firm and cautious independence of all entanglement in the European system.” He praises the American policy since 1783 of non-involvement in European wars, reinforcing that independence is vital to national security and peace. Adams insists the U.S. should avoid formal agreements in Europe, asserting that “…the organization of our government is such as not to admit of our acceding formally to that compact.” (8)

Adams argues that U.S. participation would obligate the country to take sides in European conflicts and compromise its principles. He says, “the President’s absolute and irrevocable determination” to refuse joining European alliances, firmly believing that the “…American and European systems should be kept as separate and distinct from each other as possible.” (8)

Foreign Entanglements should be… Foreign

Being a part of a sinful world, there will always be conflicts. Some conflicts are forced upon us, while most conflicts we have a choice to involve ourselves in or not. Since the founding of our nation, the U.S. has experienced many conflicts. The vision of foreign policy from our Founding Fathers and early government was to focus on independence, having national interest above ideological alignment.

The U.S. should avoid permanent foreign alliances while being prepared to defend the republic’s values and sovereignty. These insights from original sources are not merely historical—they are relevant as we navigate modern debates about international involvement. Understanding their perspective allows us to look at today’s challenges with the principles that shaped our republic.

Happy Independence Day

Andrew Nutter

- “Neutrality Proclamation, 22 April 1793,” Founders Online, National Archives

- Washington, George. “Farewell Address.” 19 Sep. 1796. Washington’s Farewell Address

- Ames, “Speech on the Jay Treaty, April 28, 1796,” in Works of Fisher Ames: With a Selection from His Speeches and Correspondence, ed. W.B. Allen and Seth Ames, Reprint, vol. 2, 2 vols. (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1984), 1142–82; “From George Washington to Thomas Pinckney, 22 May 1796,” Founders Online, National Archives.

- Ames, Fisher. “Undeclared War and Self-Defense.”The Annals of America: 1797–1820, Domestic Expansion and Foreign Entanglements, vol. 4, Encyclopedia Britannica, 1968, pp. 68–70.

- Jefferson, Thomas. “First Inaugural AddressThe Annals of America: 1797–1820, Domestic Expansion and Foreign Entanglements, vol. 4, Encyclopædia Britannica, 1968, pp. 143–146.

- Jefferson, Thomas. “The Threat of the French in Louisiana.”The Annals of America: 1797–1820, Domestic Expansion and Foreign Entanglements, vol. 4, Encyclopedia Britannica, 1968, pp. 150–152.

- Jefferson, Thomas. “Isolation and Independence.”The Annals of America: 1797–1820, Domestic Expansion and Foreign Entanglements, vol. 4, Encyclopedia Britannica, 1968, pp. 340–341.

- Adams, John Quincy.“On America and European Alliances.” The Annals of America, vol. 4, 1797–1820: Domestic Expansion and Foreign Entanglements, Encyclopædia Britannica, 1968, pp. 642–644.

Evergreen Wealth Management, LLC is a registered investment adviser. This information is for educational purposes only and does not constitute an offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities. Investments involve risk and are not guaranteed. Always consult with a qualified financial advisor or tax professional before implementing any strategy. Past performance does not guarantee future results.