Over the years I have been writing an Independence Day article to remind us of the sacrifice our founding fathers made. I truly believe few things are more important than reviewing lessons and events from history. After a year of pandemic guidelines and regulations from our government, I have never been more excited to give a history lesson about why we have the freedom we don’t deserve.

In fact, I’m so excited that I have actually written two articles. I will send out the second one during Constitution week in September.

Past Independence Day Articles:

What Does Freedom Mean – Explains the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, what our founders knew they were giving up, and the inspiring story of Nathan Hale.

The Black Robe Regiment – The name the British gave to the colonial preachers who helped fuel the fire of liberty in the colonies. I talk about the history of these famous preachers, along with three specific examples.

Founding Frenemies – The story about the great friendship & conflict of two of the most famous founders of our country. Both of them died on the same day, America’s 50th anniversary.

Divine Preservation – The story of the fascinating preservation of the “Father of the Nation” and the original Commander & Chief. Along with 4 key pillars to preserve a nation.

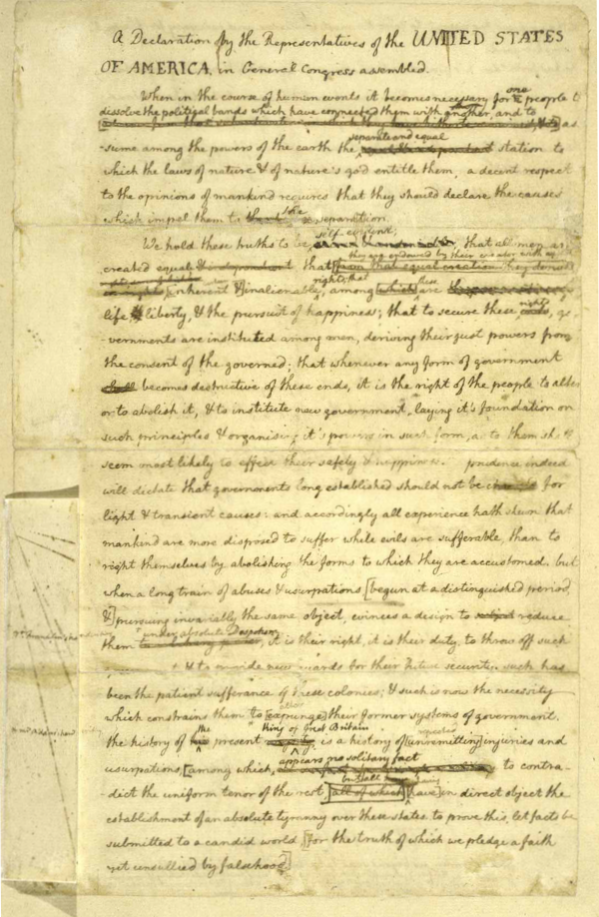

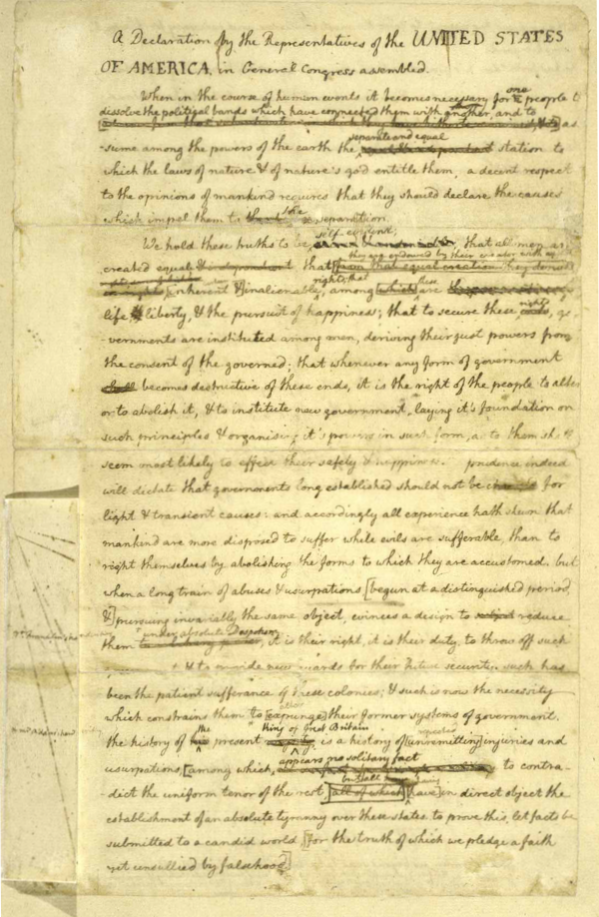

The Original Declaration of Independence

In school, we were taught that Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence. That is true, but he was not alone. The Committee of Five for the drafting of the Declaration of Independence was Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston. Thomas Jefferson was a very skilled writer and was asked to draft the first Declaration of Independence. I mentioned in my article Founding Frenemies what John Adams’ said about Jefferson writing the Declaration of Independence.

Adams later claimed that he persuaded Jefferson by telling him “I am obnoxious, suspected and unpopular. You are very much otherwise” adding, “You can write ten times better than I can.”

It’s interesting to note that Jefferson was not recognized as its original author until the 1790s. It was thought of as a collective effort by the Continental Congress. In reality, Thomas Jefferson wrote the entire document himself; he then met with Franklin and Adams of the committee to review it. Once reviewed, Franklin and Adams then made some changes, which the rest of the Committee of Five approved and presented to Continental Congress. Congress then sent this original declaration to all of the states to be unanimously approved.

Why unanimous? The Founders knew that if they didn’t unanimously approve the declaration there would be no way they could win the war because all the colonies wouldn’t be united, leaving room for King George to penetrate the movement of freedom.

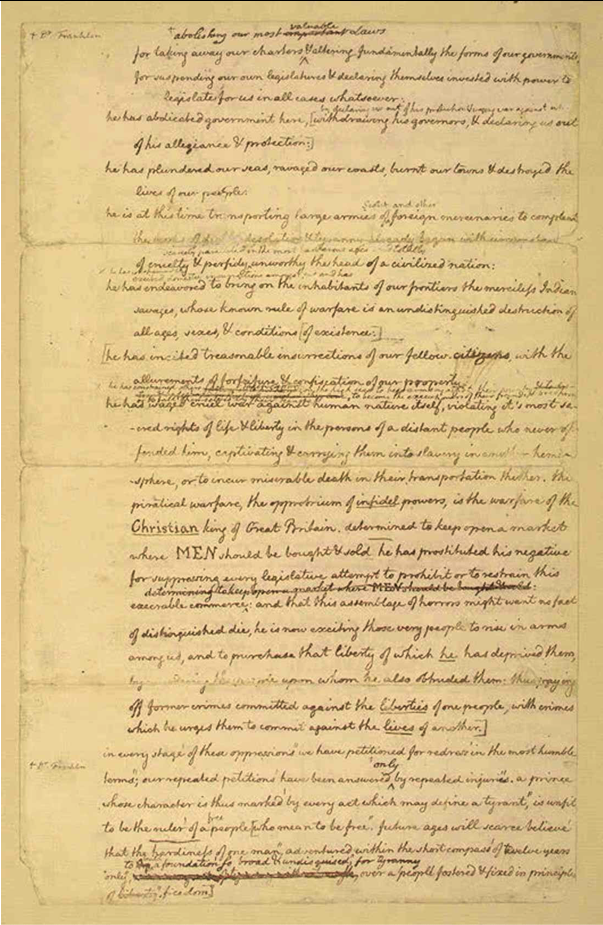

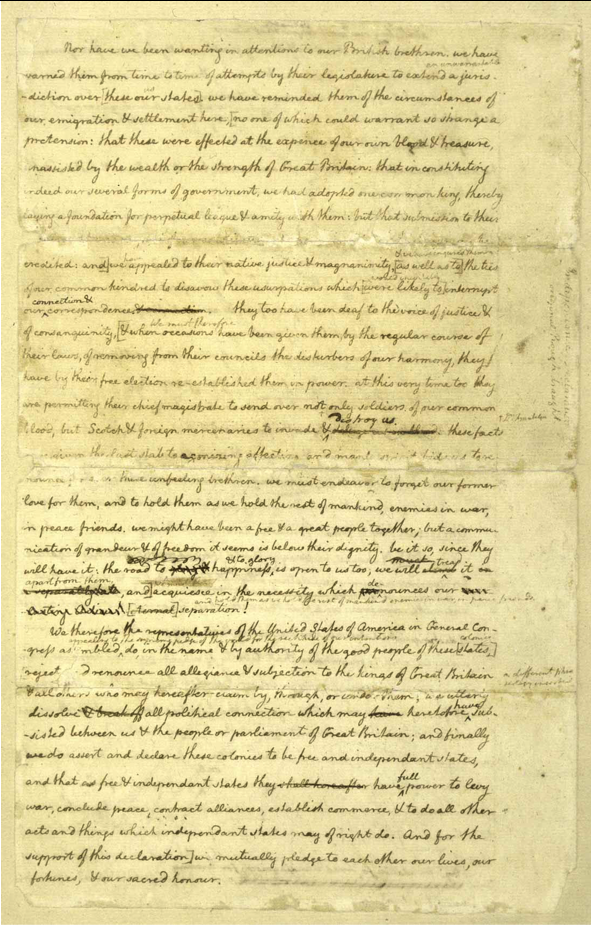

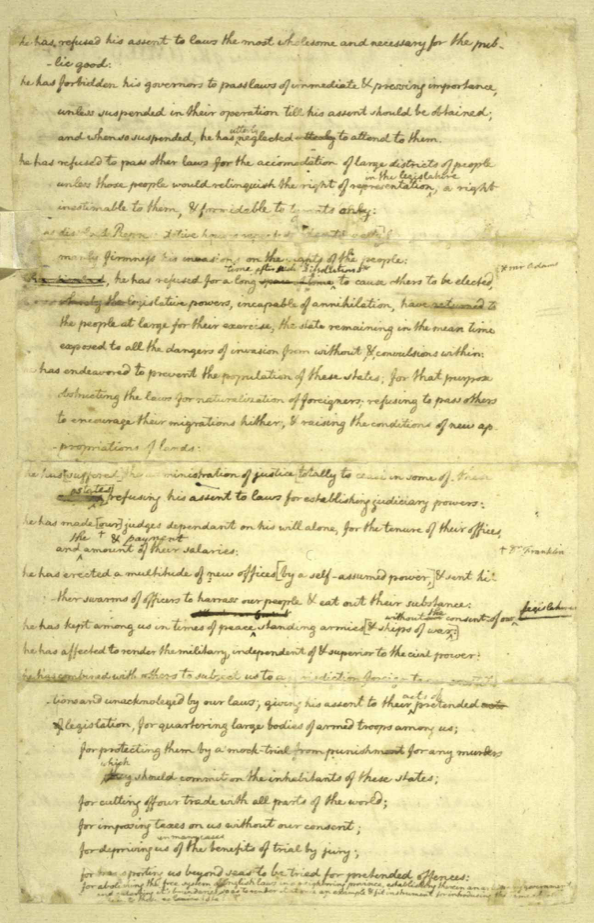

You can see here the 4 pages of the original draft. You can see the edits that Adams and Franklin made before it was submitted to congress.

Click ,HERE for a readable version of the original document.

The original draft of the Declaration of Independence was put to a vote by each of the colonies to approve. 11 colonies voted yes, 2 voted no. Changes were made to create the Declaration of Independence we have today.

What was taken out?

I can already hear you asking, “Who voted no? Why did they vote no? What needed to be changed?.”

I have outlined what was taken out and added between Jefferson’s rough draft to the final draft. Click on the pdf to read for yourself.

The majority of Jefferson’s draft was left alone. Most of the changes were subtle; like changing “sacred & undeniable” to “self-evident,” adjusting capitalizations, changing the order of words, and removing sentences that didn’t add context to condense the document. There was one change that occurred, which was the only change necessary to have unanimous approval. One of the grievances was taken out entirely.

“Grievances” in the Declaration is the list of complaints or evidence that support the colonies’ reason for separation. It’s the middle section of the Declaration, most beginning with “He has…”

South Carolina and Georgia were the states that voted no, and they did for one reason; Jefferson’s grievance on slavery.

Jefferson wrote few words in all caps or underline for emphasis. One was at the title of page one, “UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.” There are two other words in the entire document, both of which were a part of the one grievance taken out (you can see them on the third page). These words were “Christian” and “MEN”.

“He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. This piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers; is the warfare of the Christian king of Great Britain. Determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought & sold he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or to restrain this execrable commerce: and that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished die, he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them, by murdering the people upon whom he also obtruded them: thus paying off former crimes committed against the liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another.“

Christian was underlined as a mocking insult. Insisting that the King calls himself a Christian, yet has forced slavery on the colonies. In a way, Jefferson was asking, “how dare you call yourself a Christian when you support this treatment towards people?”

Men were all-caps to highlight the value of those whom the King was insulting. He didn’t use the word “slave”, as this assumes that people can be property. He made it a point to highlight that property was not being sold and that people should not be property.

The Founders and Slavery

Today we hear many claims about how our nation was founded on slavery. How could that be true if 85% of the colonies voted in agreement that slavery being brought into the colonies was a grievance? I would argue the worst grievance, and I believe Jefferson thought of that as well. Remember, this was the longest grievance he argued against and is the only one where he highlighted words of importance.

Having little time to explain, Britain established slavery in the colonies. It was the founders who were against it. The majority of the colonies tried removing slavery for decades before the revolutionary war. Henry Laurens, President of Congress, explains:

I abhor slavery. I was born in a country where slavery had been established by British Kings and Parliaments as well as by the laws of the country ages before my existence. . . . In former days there was no combating the prejudices of men supported by interest; the day, I hope, is approaching when, from principles of gratitude as well as justice, every man will strive to be foremost in showing his readiness to comply with the Golden Rule [“do unto others as you would have them do unto you” Matthew 7:12].[1]

Further…

Prior to the great Revolution, the great majority . . . of our people had been so long accustomed to the practice and convenience of having slaves that very few among them even doubted the propriety and rectitude of it.[2]

– John Jay, first Chief Justice of the United States

… a disposition to abolish slavery prevails in North America, that many of Pennsylvanians have set their slaves at liberty, and that even the Virginia Assembly have petitioned the King for permission to make a law for preventing the importation of more into that colony. This request, however, will probably not be granted as their former laws of that kind have always been repealed.[3]

– Benjamin Franklin, President of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society

The inconsistency of the institution of domestic slavery with the principles of the Declaration of Independence was seen and lamented by all the southern patriots of the Revolution; by no one with deeper and more unalterable conviction than by the author of the Declaration himself [Jefferson]. No charge of insincerity or hypocrisy can be fairly laid to their charge. Never from their lips was heard one syllable of attempt to justify the institution of slavery. They universally considered it as a reproach fastened upon them by the unnatural step-mother country [Great Britain] and they saw that before the principles of the Declaration of Independence, slavery, in common with every other mode of oppression, was destined sooner or later to be banished from the earth. Such was the undoubting conviction of Jefferson to his dying day. In the Memoir of His Life, written at the age of seventy-seven, he gave to his countrymen the solemn and emphatic warning that the day was not distant when they must hear and adopt the general emancipation of their slaves.[4]

– John Quincy Adams, also known as “hell-hound of abolition”

It would be wrong for me to continue defending our founders view on slavery when I can let them speak for themselves:

[N]ever in my life did I own a slave.[5] – John Adams

But to the eye of reason, what can be more clear than that all men have an equal right to happiness? Nature made no other distinction than that of higher or lower degrees of power of mind and body. . . . Were the talents and virtues which Heaven has bestowed on men given merely to make them more obedient drudges? . . . No! In the judgment of heaven there is no other superiority among men than a superiority of wisdom and virtue.[6]

– Samuel Adams, Signer of the Declaration, “Father of the American Revolution”

[W]hy keep alive the question of slavery? It is admitted by all to be a great evil.[7]

– Charles Carroll, Signer of the Declaration

As Congress is now to legislate for our extensive territory lately acquired, I pray to Heaven that they may build up the system of the government on the broad, strong, and sound principles of freedom. Curse not the inhabitants of those regions, and of the United States in general, with a permission to introduce bondage [slavery].[8]

– John Dickinson, Signer of the Constitution; Governor of Pennsylvania

I am glad to hear that the disposition against keeping negroes grows more general in North America. Several pieces have been lately printed here against the practice, and I hope in time it will be taken into consideration and suppressed by the legislature.[9]

– Benjamin Franklin

That mankind are all formed by the same Almighty Being, alike objects of his care, and equally designed for the enjoyment of happiness, the Christian religion teaches us to believe, and the political creed of Americans fully coincides with the position. . . . [We] earnestly entreat your serious attention to the subject of slavery – that you will be pleased to countenance the restoration of liberty to those unhappy men who alone in this land of freedom are degraded into perpetual bondage and who . . . are groaning in servile subjection.[10]

– Benjamin Franklin

That men should pray and fight for their own freedom and yet keep others in slavery is certainly acting a very inconsistent, as well as unjust and perhaps impious, part.[11]

– John Jay

The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other. . . . And with what execration [curse] should the statesman be loaded, who permitting one half the citizens thus to trample on the rights of the other. . . . And can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are of the gift of God? That they are not to be violated but with His wrath? Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just; that his justice cannot sleep forever.[12]

– Thomas Jefferson

Christianity, by introducing into Europe the truest principles of humanity, universal benevolence, and brotherly love, had happily abolished civil slavery. Let us who profess the same religion practice its precepts . . . by agreeing to this duty.[13]

– Richard Henry Lee, President of Continental Congress; Signer of the Declaration

I have seen it observed by a great writer that Christianity, by introducing into Europe the truest principles of humanity, universal benevolence, and brotherly love, had happily abolished civil slavery. Let us, who profess the same religion practice its precepts, and by agreeing to this duty convince the world that we know and practice our truest interests, and that we pay a proper regard to the dictates of justice and humanity![14]

– Richard Henry Lee

I hope we shall at last, and if it so please God I hope it may be during my life time, see this cursed thing [slavery] taken out. . . . For my part, whether in a public station or a private capacity, I shall always be prompt to contribute my assistance towards effecting so desirable an event.[15]

– William Livingston, Signer of the Constitution; Governor of New Jersey

[I]t ought to be considered that national crimes can only be and frequently are punished in this world by national punishments; and that the continuance of the slave-trade, and thus giving it a national sanction and encouragement, ought to be considered as justly exposing us to the displeasure and vengeance of Him who is equally Lord of all and who views with equal eye the poor African slave and his American master.[16]

– Luther Martin, Delegate at Constitution Convention

As much as I value a union of all the States, I would not admit the Southern States into the Union unless they agree to the discontinuance of this disgraceful trade [slavery].[17]

– George Mason, Delegate at Constitutional Convention

Honored will that State be in the annals of history which shall first abolish this violation of the rights of mankind.[18]

– Joseph Reed, Revolutionary Officer; Governor of Pennsylvania

Domestic slavery is repugnant to the principles of Christianity. . . . It is rebellion against the authority of a common Father. It is a practical denial of the extent and efficacy of the death of a common Savior. It is an usurpation of the prerogative of the great Sovereign of the universe who has solemnly claimed an exclusive property in the souls of men.[19]

– Benjamin Rush, Signer of the Declaration, Founder of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, President of the National Abolition Movement

The commerce in African slaves has breathed its last in Pennsylvania. I shall send you a copy of our late law respecting that trade as soon as it is published. I am encouraged by the success that has finally attended the exertions of the friends of universal freedom and justice.[20]

– Benjamin Rush

Justice and humanity require it [the end of slavery]–Christianity commands it. Let every benevolent . . . pray for the glorious period when the last slave who fights for freedom shall be restored to the possession of that inestimable right.[21]

– Noah Webster, Responsible for Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution

Slavery, or an absolute and unlimited power in the master over the life and fortune of the slave, is unauthorized by the common law. . . . The reasons which we sometimes see assigned for the origin and the continuance of slavery appear, when examined to the bottom, to be built upon a false foundation. In the enjoyment of their persons and of their property, the common law protects all.[22]

– James Wilson, Signer of the Constitution; U. S. Supreme Court Justice

[I]t is certainly unlawful to make inroads upon others . . . and take away their liberty by no better means than superior power.[23]

– John Witherspoon, Signer of the Declaration

I can only say that there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it [slavery].[24]

– George Washington

To further emphasize the majority of our founding fathers were against slavery, Abolishment of slavery started within some states before we even won the revolutionary war;

1780 – Pennsylvania & Massachusetts [25]

1784 – Connecticut & Rhode Island [26]

1786 – Vermont [27]

1792 – New Hampshire [28]

1799 – New York [29]

1804 – New Jersey [30]

Slavery couldn’t continue in any federal territory like the Northwest Territory (Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Iowa, & Wisconsin) because it was prohibited by Congressional act in 1789;[33] Signed into law by George Washington. Something that only could happen if the majority of Congress agreed.

In 1794 the exportation of slaves from any state was banned,[34] and in 1808 the importation of slaves into any state was also banned.[35]. After the Revolutionary War, the movement to end slavery in the new United States of America moved faster at that time than any other nation in the world.[36]

The 3/5ths Compromise explained

The Constitution of the United States was adopted in 1788. In Article 1, Section 2; the Constitution explains how representatives are counted in each state. It states,

“… determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three-fifths of all other Persons.”

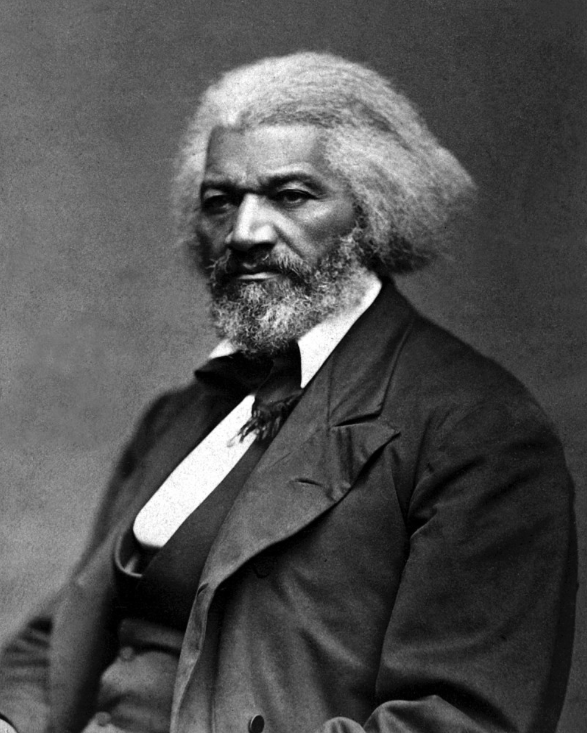

This is used by many as evidence to suggest that the Founders only viewed African Americans as 3/5ths of a person. This is simply not the case. Let’s hear this explained by abolitionist Frederick Douglas.

The 3/5ths compromise was implemented in the constitution to limit the representation of the southern slave states. Slave states were against the compromise, while anti-slavery states argued to limit the congressional power of those slave states. If an African American was free, he was counted as a whole person.

Frederick Douglas loved our foundering fathers and their efforts to abolish slavery. When he was younger he didn’t believe this, but when he got older he did his own research (something all of us should do more often.) He said,

My new circumstances compelled me to re-think the whole subject, and to study, with some care. . . . By such a course of thought and reading, I was conducted to the conclusion that the Constitution of the United States . . . not only contained no guarantees in favor of slavery, but, on the contrary, was in its letter and spirit an anti-slavery instrument.[32]

So why was slavery continued?

The sad truth is, the issue of slavery in the United States of America went in the wrong direction after most of our Founding Fathers died.

Elias Boudinot – a president of Congress during the Revolution – warned that this new direction by Congress would, “bring an end to the happiness of the United States.”[39] John Adams said in a letter to Thomas Jefferson in 1819 that stopping the slavery prohibition would destroy America.[40]

North Carolina and Maryland would reverse their voting policies and limited voting to whites only. The Missouri Compromise was passed in 1820, which permitted the admission of new slave-holding states.[37] Congress had to legislate this “compromise” because it went against all the legislation from Congress during the time of our Founding Fathers. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 allowed southern slaveholders to go North to kidnap runaway slaves. The Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854 allowed slavery into the new territory of what is now Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, North & South Dakota, Kansas, and Nebraska.[38]

Finally, the huge blow against the anti-slavery movement was the Dred Scott decision; deciding that the United States Constitution was not meant to include citizenship for people of African descent. This Supreme Court ruling completely overstepped its constitutional power. This would result in a huge wave of support for the newly formed and anti-slavery Republican Party. This great nation, unfortunately had to settle this debate with a Civil War that cost over 600,000 lives. After the end of the Civil War and the passage of the 13th and 14th Amendment, most of the pro-slavery policies in the Country were reversed.

Conclusion

Thomas Jefferson was appalled in the new direction the nation was taking after his time in office. He wrote a letter in 1820 where he mentioned the pro-slavery movement taking place, “In the gloomiest moment of the Revolutionary War, I never had any apprehensions equal to what I feel from this source.”[41] Thomas Jefferson was more horrified about the rise of pro-slavery in America than he was during any moment of the Revolutionary War.

The United States of America does have a complicated history concerning slavery. It is, however, a great and important history to tell. Great abolitionists like Frederick Douglas and Martin Luther King Jr. would quote our Founding Fathers often to support their movement. The spirit of the vast majority of our Founding Fathers was ANTI-SLAVERY. Let us continue to embody the amazing values our Founding Fathers possessed to make our nation a more perfect union.

Evergreen Wealth Management, LLC is a registered investment adviser. Information presented is for educational purposes only and does not intend to make an offer or solicitation for the sale or purchase of any specific securities, investments, or investment strategies. Investments involve risk and unless otherwise stated, are not guaranteed. Be sure to first consult with a qualified financial adviser and/or tax professional before implementing any strategy discussed herein. Past performance is not indicative of future performance.

Special Thanks to Wallbuilders for their collection of original documents of American history.

1. Frank Moore, Materials for History Printed From Original

Manuscripts, the Correspondence of Henry Laurens of South Carolina (New York: Zenger Club, 1861), p. 20, to John Laurens on August 14, 1776.

2. John Jay, The Correspondence and Public Papers of John Jay, Henry P. Johnston, editor (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1891), Vol. III, p. 342, to the English Anti-Slavery Society in June 1788.

3. Benjamin Franklin, The Works of Benjamin Franklin, Jared Sparks, editor (Boston: Tappan, Whittemore, and Mason, 1839), Vol. VIII, p. 42, to the Rev. Dean Woodward on April 10, 1773.

4. John Quincy Adams, An Oration Delivered Before the Inhabitants of the Town of Newburyport at Their Request on the Sixty-First Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1837 (Newburyport: Charles Whipple, 1837), p. 50.

5. John Adams, The Works of John Adams, Charles Francis Adams, editor (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1854) Vol. IX, p. 92, letter to George Churchman and Jacob Lindley on January 24, 1801.

6. Samuel Adams, An Oration Delivered at the State House, in Philadelphia, to a Very Numerous audience; on Thursday the 1st of August, 1776 (London: E. Johnson, 1776), pp. 4-6.

7. Kate Mason Rowland, Life and Correspondence of Charles Carroll of Carrollton (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1898), Vol. II, p. 321, to Robert Goodloe Harper on April 23, 1820.

8. Charles J. Stille, The Life and Times of John Dickinson(Philadelphia: J. P. Lippincott Company, 1891), p. 324, to George Logan on January 30, 1804.

9. Benjamin Franklin, The Works of Benjamin Franklin, John Bigelow, editor (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), Vol. 5. p. 356, letter to Mr. Anthony Benezet on August 22, 1772.

10. Annals of Congress, Joseph Gales, Sr., editor (Washington: Gales and Seaton, 1834), Vol. 1, pp. 1239-1240, Memorial from the Pennsylvania Abolition Society from February 3, 1790 presented to Congress on February 12, 1790.

11.John Jay, The Life and Times of John Jay, William Jay, editor (New York: J. & S. Harper, 1833), Vol. II, p. 174, to the Rev. Dr. Richard Price on September 27, 1785.

12. 17. Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia(Philadelphia: Matthew Carey, 1794), Query XVIII, pp. 236-237.

13. Richard Henry Lee, Memoir of the Life of Richard Henry Lee, Richard Henry Lee, editor (Philadelphia: H. C. Carey and I. Lea, 1825), Vol. I, p. 19, the first speech of Richard Henry Lee in the House of Burgesses of Virginia.

14. Richard H. Lee (Grandson), Memoir of the Life of Richard Henry Lee (Philadelphia: H. C. Carey and I. Lea, 1825), Vol. 1, pp. 17-19, the first speech of Richard Henry Lee in the House of Burgesses of Virginia.

15. William Livingston, The Papers of William Livingston, Carl E. Prince, editor (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1988), Vol. V, p. 358, to James Pemberton on October 20, 1788.

16. Luther Martin, The Genuine Information Delivered to the Legislature of the State of Maryland Relative to the Proceedings of the General Convention Lately Held at Philadelphia (Philadelphia: Eleazor Oswald, 1788), p. 57. See alsoDebates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution, Jonathan Elliot, editor (Washington, D. C.: 1836), Vol. I, p. 374.

17. Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution, Jonathan Elliot, editor (Washington, D. C.: 1836), Vol. III, pp. 452-454, George Mason, June 15, 1788.

18. William Armor, Lives of the Governors of Pennsylvania(Norwich, CT: T. H. Davis & Co., 1874), p. 223.

19. Benjamin Rush, Minutes of the Proceedings of a Convention of Delegates from the Abolition Societies Established in Different Parts of the United States Assembled at Philadelphia (Philadelphia: Zachariah Poulson, 1794), p. 24.

20. Benjamin Rush, Letters of Benjamin Rush, L. H. Butterfield, editor (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1951), Vol. 1, p. 371, to Richard Price on October 15, 1785.

21.Noah Webster, Effect of Slavery on Morals and Industry (Hartford: Hudson and Goodwin, 1793), p. 48.

22. James Wilson, The Works of the Honorable James Wilson, Bird Wilson, editor (Philadelphia: Lorenzo Press, 1804), Vol. II, p. 488, lecture on “The Natural Rights of Individuals.”

23. John Witherspoon, The Works of John Witherspoon (Edinburgh: J. Ogle, 1815), Vol. VII, p. 81, from “Lectures on Moral Philosophy,” Lecture X on Politics.

24. George Washington, The Writings of George Washington, John C. Fitzpatrick, editor (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1932), Vol. XXVIII, pp. 407-408, to Robert Morris on April 12, 1786.

25. A Constitution or Frame of Government Agreed Upon by the Delegates of the People of the State of Massachusetts-Bay (Boston: Benjamin Edes and Sons, 1780), p. 7, Article I, “Declaration of Rights” and An Abridgement of the Laws of Pennsylvania, Collinson Read, editor, (Philadelphia: 1801), pp. 264-266, Act of March 1, 1780.

26. The Public Statue Laws of the State of Connecticut (Hartford: Hudson and Goodwin, 1808), Book I, pp. 623-625, Act passed in October 1777 and Rhode Island Session Laws (Providence: Wheeler, 1784), pp. 7-8, Act of February 27, 1784.

27. The Constitutions of the Sixteen States (Boston: Manning and Loring, 1797), p. 249, Vermont, 1786, Article I, “Declaration of Rights.”

28. Constitutions of the Sixteen State (Boston: Manning and Loring, 1797), p. 50, New Hampshire, 1792, Article I, “Bill of Rights.”

29. Laws of the State of New York, Passed at the Twenty-Second Session, Second Meeting of the Legislature(Albany: Loring Andrew, 1798), pp. 721-723, Act passed on March 29, 1799.

30. Laws of the State of New Jersey, Compiled and Published Under the Authority of the Legislature, Joseph Bloomfield, editor (Trenton: James J. Wilson, 1811), pp. 103-105, Act passed February 15, 1804.

31. Walter E. Williams, Creators Syndicate, Inc., May 26, 1993, “Some Fathers Fought Slavery.”

32. Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, (New York: Collier Books, reprint 1893 of an 1888 original), p. 705.

33. Debates and Proceedings in the Congress of the United States (Washington, DC: Gales and Seaton, 1834), Vol. II, p. 2215, 1789, “An act to provide for the government of the Territory northwest of the river Ohio”; see alsoThe Constitutions of the United States of America (Trenton: William and David Robinson, 1813), p. 366, “Northwest Ordinance,” Article #6.

34. Debates and Proceedings (1849), p. 1425, “An act to prohibit the carrying on the slave-trade from the United States to any foreign place or country” in 1794.

35. Debates and Proceedings (1849), p. 1266, “An act to prohibit the importation of slaves into any port or place within the jurisdiction of the United States” in 1807.

36. Cobb, An Inquiry into the Law of Negro Slavery, pp. 153, 163, 169.

37. Debates and Proceedings (1849), pp. 2555, 2559, “An act to authorize the people of Missouri Territory to form a constitution and state government” in 1820.

38. Statutes at Large and Treaties of the United States of America, from December 1, 1851, to March 3, 1855, George Minot, editor (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1855), 33rd Congress, 1st Session, Chapter 59, May 30, 1854, Vol. 10, pp. 277-290.

39. George Adams Boyd, Elias Boudinot (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), p. 290, in a letter to Elias Boudinot on November 27, 1819.

40. Charles Francis Adams, The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1856), p. 386, in a letter to Thomas Jefferson on December 18, 1819.

41.Thomas Jefferson, The Works of Thomas Jefferson (New York and London: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1905), p. 157, in a letter to Hugh Nelson on February 7, 1820