A client recently asked me how I felt about a top 10 mutual fund list, which shows the top performing mutual funds from a 1, 3, 5 or 10-year periods. I said, “For the most part, they are meaningless.”

I think the client knew I was not a fan, but he seemed surprised by my answer. I quickly clarified, “It’s not that the list themselves are meaningless, but more often then not people look at these lists to pick their next mutual fund (ETF, Stock, etc.) to buy. Investment managers make it to the top of these lists all the time by accident.”

Accident? Is it crazy for me to say that? How does an investment manager accidentally make it to the top? I think there are 3 possible reasons why a mutual fund (or fund manager) would make it on a list like this.

-

Pure Accident

-

The Right Place at the Right Time

-

The True Success Stories

Pure Accident

Sometimes a mutual fund makes it on a “top 10” list by tracking an index or a predetermined measurement that has abnormal price movement. Most of the time the purpose of the fund was never to beat stock market averages. These almost never make it on a 10-year top ten list but happens all the time on a 1 or 3-year list. For example, some funds track the 3 times daily movement of gold miner stocks. Some periods they beat the overall return of the stock market, but that wasn’t the intent of the investment manager(s). Their intent was just to increase the daily volatility of gold mining stocks.

Right Place at the Right Time

This list, in my opinion, is sadly the majority who make it on a top 10 fund manager list. These managers had an objective to experience high returns and accomplished their goal. Their management style was dramatically different then everyone else’s and their style “won.” After their period of outperformance, they failed to recognize the reason for their success. They believe it’s purely their good decision making, when more often then not it’s just that their style of management was favored by the market during that period of time. When this happens long term underperformance occurs. The managers’ style doesn’t change because he or she didn’t realize where the success came from.

For example, let’s look at Morningstar’s Manager of the Decade award (Morningstar Press Release) for domestic equities in 2010. The vote wasn’t entirely on performance, but their performance against the managers’ benchmark was a major factor. Every manager who was a final nominee for domestic equities didn’t perform at all as they did against their benchmark since 2010. In fact, all but one has clearly underperformed their benchmark since 2010. (1) Let’s focus only on the winner, Bruce Berkowitz of the Fairholme Fund(FAIRX). His performance vs. the market since his award hasn’t gone well. In fact as of today, 03/07/19, Morningstar currently ranks the Fairholme Fund in the 100th percentile of total return on a 3, 5, and 10-year basis (see here).

Data comes from Ycharts, a graph of ticker symbol FAIRX versus S&P500 index from 01/01/2010-02/19/2019.

If we annualized his return versus the S&P 500 it would be 3.42% versus 12.85% respectively. Bruce highly concentrated on companies he liked, which worked well for him between 2000-2009. Since 2010, he placed heavy concentration on retailer Sears, real estate firm The St. Joe Company & preferred securities of Fannie Mae & Freddie Mac.(1) Bruce says I’ve always been “value-based”, then he gets specific, “I’ve always been a balance sheet buyer.”(2) That means he tries to buy a company at a significant discount then what he thinks the assets of the company is worth. In other words, buying a $1.00 for $0.50.

Bottom line is his style of analysis and what he focused on became out of favor or misguided with the market. Managers in this category can often make unreasonable bets because of a past success they had while not understanding the reason why.

True Success Stories

When people are looking for managers to invest their money, this is the list they are looking for. Managers who can perform well over long periods of time in almost any time period. This, of course, is extremely difficult. This list of men and women not only looks in the past of what was successful, but they understand all of the drivers of return and can competently invest looking at realistic outcomes in the future. Sadly, most of these managers don’t make a top ten list. They are however consistently in the top 30% of most time periods. My favorite investor, Charlie Munger, falls into this category and I would like to briefly talk about him.

Charlie is best known for being the vice chairmen of Berkshire Hathaway and Warren Buffet’s right-hand man for 50+ years. In the investment community, people know him for his witty wisdom. So much so that someone wrote a book titled, Poor Charlie’s Almanack: The Wit and wisdom of Charles T. Munger. On May 5, 2018, I went to the Berkshire Hathaway Annual Shareholders meeting with a couple of co-workers. Warren Buffet said at the meeting, “Charlie has been a wonderful teacher for me.” Below are some of my favorite quotes from and about Charlie.

“If you’re going to live a long time, you have to keep learning—what you formerly knew is never enough. So if you don’t learn to constantly revise your earlier conclusions, and get better ones, you are…—I always use the same metaphor—you’re like a one-legged man in an ass-kicking contest.”

At the 2018 Berkshire shareholder meeting, someone asked Charlie for a formula to determine if a stock is undervalued or not. – “I can’t give you a formulaic approach, because I don’t use one. And I just mix all the factors and if the gap between value and price is not attractive, I go on to something else… But that’s not a formula. If you want a formula, you should go back to graduate school. They’ll give you lots of formulas that won’t work.”

“It’s far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price. Charlie understood this early; I was a slow learner.” – Warren Buffet

“It’s remarkable how much long-term advantage people like us have gotten by trying to be consistently not stupid, instead of trying to be very intelligent. There must be some wisdom in the folks saying, ‘It’s the strong swimmers who drown.’”

“There’s a rule of fishing that’s a very good rule. And the first rule of fishing is ‘fish where the fish are.’ And the second rule of fishing is ‘don’t forget the first rule,’ Investing is the same thing. And some places have lots of fish and you don’t have to be that good of a fisherman to do pretty well. Other places are so heavily fished that no matter how good a fisherman you are, you aren’t going to do very well.”

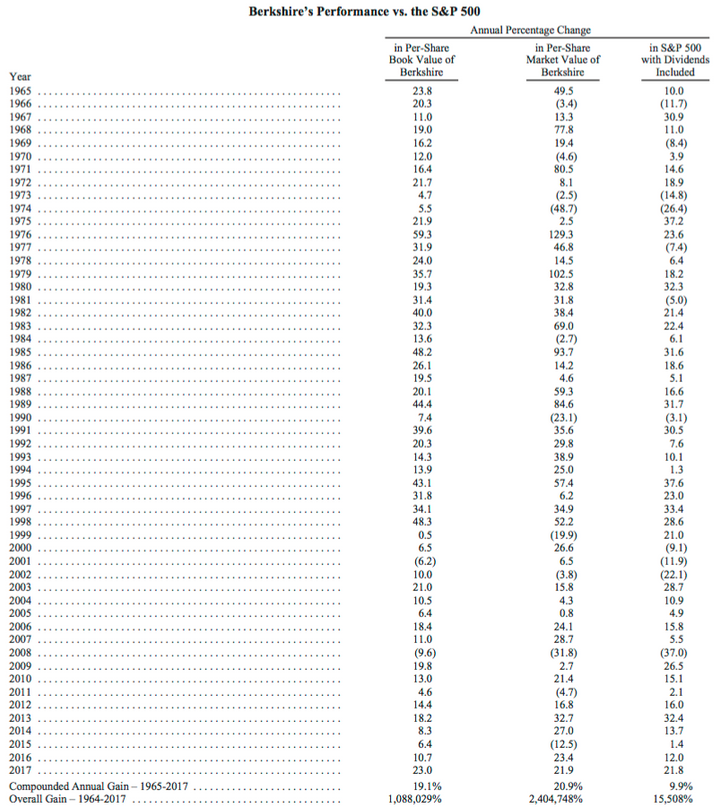

Looking at his investment performance, Charlie Munger’s first fund from 1962-1975 had outperformed his benchmark, with a compounded annual return of 19.82% versus the Dow annual return of 5%. (3) Charlie joined Warren at Berkshire as Vice Chairmen. The chart on the right shows the stock’s performance.

This is just a small snapshot of the investment performance of Charlie. His success at Berkshire, Wesco Financial, Daily Journal, etc., shows that the success of his first fund in 1962 wasn’t an accident. Unlike Bruce Berkowitz, Charlie’s understanding of investment success allows him to be a successful investor in any time period. In Charlie’s case, 5+ decades.

These couple quotes and examples are just a small sample that supports my claim that Charlie Munger is someone that can recognize the reasons for success in investing.

Conclusion

Does this mean Charlie has never made an investment mistake? Absolutely not. He would be the first to admit it. Every great investor makes mistakes just like every great baseball player strikes out. When we strike out or make a mistake are we able to understand why? Just like when we have success do we understand why? We want to understand all drivers of success and not be blind when we were just in the right place at the right time.

Everyone can learn from this. What area’s in our career, or in life, do we blind ourselves from? When things are going well do we assume it’s because of all the right things we are doing? Just like our second category of investors, when something goes well we immediately think of all the reason’s why WE made it happen. There is nothing wrong with being in the right place at the right time. The problem comes when we are at the right place at the right time, but we are blind about it and think it happened purely because of our good decision(s).

As investment managers, Steve and I will make some good and some bad decisions. I think we do a great job at limiting our mistakes by “trying to be consistently not stupid, instead of trying to be very intelligent”, to quote Charlie. When the decisions we make are good we avoid the mistake of assuming every good decision is from perfect execution. We look into the success and try to understand the reason for it. Sometimes they happen because we were at the right place at the right time. Our goal is not to be blind about it when that happens. Our ultimate goal is not to make sure we make it on a top 10 list, but provide consistent returns that can meet our client(s) objectives. In order for us to recognize the reason for success I have to quote Charlie again, we need to “constantly revise [our] earlier conclusions, and get better ones.”

1) Article by John Coumarious in Oct. 2018. Was apart of the selection process of the 2009 Morningstar Manager of the Decade. Click HERE.

2) Interview Bruce had with Bloomberg Markets in 2017. They talked about his recent underperformance and how he manages his fund. Click HERE

3) Janet Lowe, Damn Right! Behind the Scenes with Berkshire Hathaway Billionaire Charlie Munger (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2000).

Evergreen Wealth Management, LLC is a registered investment adviser. Information presented is for educational purposes only and does not intend to make an offer or solicitation for the sale or purchase of any specific securities, investments, or investment strategies. Investments involve risk and unless otherwise stated, are not guaranteed. Be sure to first consult with a qualified financial adviser and/or tax professional before implementing any strategy discussed herein. Past performance is not indicative of future performance.