One of my favorite topics to research, learn, and talk about is the founding of the United States of America. I have the highest respect for our founding fathers. Collectively, they put together what would become the freest and most prosperous country the world has ever known.

As some of you know, each year I write an article before July 4th to celebrate Independence Day. The articles focus on events or topics I feel most Americans have never heard of. The first article, What Does Freedom Mean, explains the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, what our founders knew they were giving up when they signed that document, and the inspiring story of Nathan Hale. The second article, The Black Robe Regiment, is the name the British gave to the colonial preachers who helped fuel the fire of liberty in the colonies. I talk about the history of these famous pastors, along with three specific examples of how they influenced the founding of our great country.

For this article, we want to explore two of the most famous founding fathers, with a twist that you maybe never heard of before.

Presidents Who Signed The Declaration of Independence

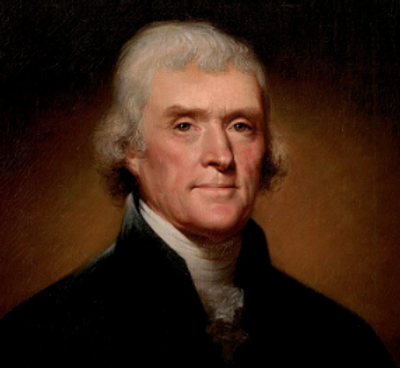

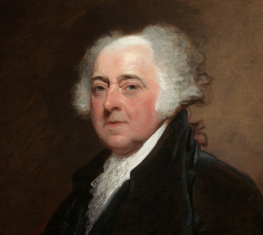

Thomas Jefferson and John Adams are the only two presidents who signed the Declaration of Independence. In 1775, both men were sent by their respective colonies to serve as delegates in Philadelphia’s second Continental Congress. That summer was the first time Adams and Jefferson were introduced to each other. Adams first impression of Jefferson was, “Though a silent member in Congress, [Mr. Jefferson] was so prompt, frank, explicit, and decisive upon committees and in conversation … that he soon seized upon my heart” he’d recall in 1822.(1)

They were both appointed to the Committee of Five on July 11, 1776, a group put together to write a written statement that would make the definitive case for colonial independence. Jefferson was chosen to write the first draft of the Declaration of Independence. Adams later claimed that he persuaded Jefferson by telling him “I am obnoxious, suspected and unpopular. You are very much otherwise” adding, “You can write ten times better than I can.”(1) Jefferson acknowledged Adams as the Declaration’s “pillar of support on the floor of Congress, its ablest advocate, and defender.“(2.1)

Founding Frenemies

Adams was sent to France in 1778 to champion the revolutionary cause, and after the war served as the first ambassador in Britain from 1785-1788. Jefferson went to France in 1784 and became friends with the entire Adams family. Jefferson also would travel with Adams in the United Kingdom while he was the first ambassador. They became great friends during this time period.

Conflicts between Jefferson and Adams started during George Washington’s presidency of 1789-1797. Adams was the Vice President in both of Washington’s terms, which made him President over the United States Senate. Adams was heavily involved in both persuading senatorial procedure, policy and persuading votes against legislation he opposed. He would cast at least 29 tie-breaking votes in the Senate, unheard of in today’s politics.(2) Although Adams would proclaim he was above political parties like Washington, he almost always sided with the Federalist parties view of a stronger federal government. This was contrary to the Democratic-Republican parties view fearing government power, which was lead and founded by Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson was Washington’s Secretary of State but resigned in 1793. After his resignation, the relationship began to erode, which is supported by letters we have of Adams starting to gossip about Jefferson to his sons John Quincy and Charles.(3)

Although neither Adams or Jefferson ran a full campaign in the 1796 election, their supporters certainly did. The Federalist press labeled Jefferson a Francophile, questioned his courage during the War of Independence, and charged that he was an atheist. Adams was portrayed as a monarchist and an Anglophile who was secretly bent on establishing a family dynasty by having his son succeed him as President.(4) Adams ended up winning the Presidency and Jefferson elected as Vice President.

Why was Jefferson elected as VP? At the time, each member of the Electoral College cast two electoral votes, with no distinction made between electoral votes for president and electoral votes for vice president. The presidential candidate receiving the greatest number of votes was elected president, while the presidential candidate receiving the second-most votes was elected vice president. That was changed after the 12th Amendment was ratified (oddly enough, in 1804 during Jefferson’s first term). Click HERE to learn more.

Things got worst during Adams presidency leading up to the 1800 election. In 1798 Jefferson was disgusted by the Alien and Sedition Acts led by President Adams. Jefferson would go behind Adams’s back by drafting the “Kentucky Resolution,” passing his work along to allies in the State. The resolution passed that November.(1) Jefferson’s party portrayed Adams as a monarchist and the Federalist Party as an enemy of republicanism, including the greater egalitarianism promised by the American Revolution. The Federalists depicted Jefferson as a godless nonbeliever and a radical revolutionary; he was often called a Jacobin, the most radical faction in France during the French Revolution. His election was charged that it will bring about a reign of terror in the nation.(4)

The level of personal attacks by both was endless. At one point, Adams was accused of plotting to have his son marry one of the daughters of King George III that would establish a dynasty to unite Britain and the United States. Jefferson, meanwhile, was accused of vivisection and of conducting bizarre ritualistic rites at Monticello, his home in Virginia.(4)

After Jefferson won the vigorous election of 1800, Adams refused to attend the inauguration.

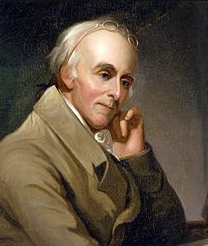

Benjamin Rush had a dream about John Adams and Thomas Jefferson

Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration, was still friends with both Adams and Jefferson. He was troubled by the separation of Jefferson and Adams. One-night, several months after Jefferson’s retirement from the Presidency in 1809, Dr. Rush had a dream about the two which he felt was important. On October 17, 1809, he wrote down an account of that dream and sent it to John Adams. In describing the dream he said he had seen Adams and Jefferson reunite, become good friends, and both “sunk into the grave nearly at the same time, full of years and rich in the gratitude and praises of their country.”(5)

Click HERE to read the incredible dream Rush had.

At the time this letter was written, Jefferson and Adams were very upset with each other. None of what was described in Dr. Rush’s letter had happened, or seem likely that it ever would. Nevertheless, Adams, and later Jefferson, received the dream from their dear friend with an open heart.(6) (Click HERE to read the response Adams gave to Dr. Rush) Jefferson would first reach out to Adams with a gracious letter. Adams, just as he told Rush, did “not fail to acknowledge and answer the letter.”(7) This was the start of an amazing friendship reuniting.

There were amazing accuracy and future fulfillment of several parts of Dr. Rush’s dream. As accurately described in his dream, Adams and Jefferson did again become close friends, which did follow the “correspondence of several years” described in the dream. Furthermore, the “world was favored with a sight of the letters” as entire volumes were eventually published which contained the letters written between those two in their later years.(6)

Most interesting, seventeen years after his dream, they did “sink into the grave nearly at the same time” as the two men died within hours of each other on the same day: July 4th, 1826 – the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence!

Both expired “full of years and rich in the gratitude of praises of their country.”(5)

Happy Independence Day!

1) “The Greatest Frenemies in Political History.” Mental Floss, 22 Feb. 2016, mentalfloss.com/article/75839/greatest-frenemies-political-history.

2) Linda Dudik Guerrero, in her study of Adams’ vice presidency, found that Adams cast “at least” thirty one votes, a figure accepted by Adams’ most recent biographer. The Senate Historical Office has been able to verify only twenty-nine tie -breaking votes by Adams.

2.1) Hatfield, Mark O. “John Adams, 1st Vice President (1789-1797).” U.S. Senate: John Adams, 1st Vice President (1789-1797), United States Senate, 5 MAr. 2018, www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/VP_John_Adams.htm

3) Pruitt, Sarah. “Jefferson & Adams: Founding Frenemies.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 1 Nov. 2016, www.history.com/news/jefferson-adams-founding-frenemies

4) Taylor, James C. “John Adams: Campaigns and Elections.” Miller Center, The University of Virginia, 19 June 2017, millercenter.org/president/adams/campaigns-and-elections

5) Benjamin Rush, Letters of Benjamin Rush, L. H. Butterfield, editor (Princeton: The American Philosophical Society, 1951), Vol. II, pp. 1021-1022, to John Adams on October 17, 1809.

6) Barton, David. “Benjamin Rush Dream about John Adams and Thomas Jefferson.” WallBuilders, WallBuilders.com, 1 June 2018, wallbuilders.com/benjamin-rush-dream-john-adams-thomas-jefferson/

7) From a handwritten letter from John Adams to Benjamin Rush, dated from Quincy [Massachusetts], December 21, 1809, in possession of the author.

Evergreen Wealth Management, LLC is a registered investment adviser. Information presented is for educational purposes only and does not intend to make an offer or solicitation for the sale or purchase of any specific securities, investments, or investment strategies. Investments involve risk and unless otherwise stated, are not guaranteed. Be sure to first consult with a qualified financial adviser and/or tax professional before implementing any strategy discussed herein. Past performance is not indicative of future performance.